At first, Addie wasn’t sure what it was. It didn’t look exactly like anything she’d ever seen. But when she picked it up and turned it over in her hand, it was as plain as anything that it was a fish.

Or more like the distilled, concentrated idea of a fish—a fish shown the way it might think of itself, if you could imagine such a thing. How could wood be made to do the things this piece of wood did?

She’d found the smooth, polished curve of linden lying on the corner of her porch, in the same place she had taken to leaving treats for Ned Overby on the days George Hutto drove him back from the YMCA. She’d found it last Tuesday morning as she was sweeping; she guessed it had lain there since the previous Saturday. The linden, almost bone-white, made little contrast with the whitewashed porch planking. If she hadn’t scooted the carving with the broom, she might never have noticed it.

She smiled as she looked at it now. She’d placed it on her mantle in the parlor. It soothed her eyes from the strain of her candle-wicking. The flow and bend of it invited her hand like an old friend.

She was almost finished with this bedspread. Just one more corner of the pattern to stitch and then it would be ready to wash and dry and take to Dub.

She was still surprised at how quickly the spreads sold. She could tell, at first, that Dub only let her put the spread in his store as a family favor—or maybe to keep from having to put up with Lou’s displeasure. But it sold within the week. After she gave Dub the store’s share—over his protests—she still had more than three dollars left over. And the next piece sold just as quickly. And the next. Dub soon stopped trying to act like he didn’t care about the money and started asking her how soon she could get the next bedspread on his shelf. Mr. Peabody had recently offered to start having one of his boys drive out with her cloth and thread and notions, and he let her know if she needed a few days on credit, that’d be just fine.

Addie was leery of credit, though. She liked the thought of the money in the ginger jar in the back of her closet, and she especially liked knowing all of it belonged to her, to do with as she saw fit. Credit muddied the water.

The Ingraham clicked and rattled, then struck. Ten o’clock—the mail was probably here. She finished out the row she was on and laid aside the cloth. She went to the front door, brushing her hand across the fish’s back as she passed the mantle.

She stepped out onto the front porch. A meadowlark sat on the top rail of the lane fence. Its black necklace puffed out, dark against the yellow breast, every time it piped. She came down the steps, and the meadowlark blurred away toward the tree line.

The sound of hammers battered at the clear midmorning air. James Potts had sold off a piece of his pasture fronting the road, and somebody was building a big house on it. Every fair day since early spring she’d been waking to the sound of the project, first the sawing and shouting as they cut down enough of the big sweet gums and ashes to make a notch in the woods for the house to sit in. She’d watched as they leveled the plot, then watched the frame go up and the clapboard siding wrap slowly around the house. Now they were nailing down the roof planking. One of these days, Addie knew, she needed to find out who her new neighbors were going to be. Not that she minded neighbors. It’d be a comfort, in a way. And it would sure be nice if they had a little girl about Mary Alice’s age. Take some of the pressure off.

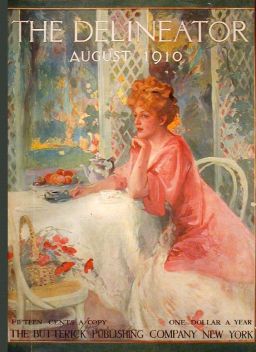

Good. Her summer Delineator was in the mailbox. Beneath it was an ivory–colored envelope addressed in a very decorative hand. She ran her thumb beneath the flap and opened it. An invitation to Callie Watson’s wedding.

Addie looked down the road, tapping the invitation against her palm. In a little while, she dropped it into the pocket of her apron and started back toward the house, thumbing through the Delineator as she went.

The magazine was a bit of an indulgence, she guessed, but one she thought she could afford. Looking at the smart fashion plates and reading the elegant descriptions of each costume allowed her to dream a little, to imagine herself able to pick and choose among the delightful outfits for herself and her children, just like the ladies in town who lived on Cameron Hill, whose daughters went to Epworth League and whose husbands came home every night to sit in an armchair and smoke and read the paper. The Delineator was an hour or two of pleasant escape, delivered to her mailbox four times a year. Not a bad bargain for twenty–five cents per annum.

She went back in the house and dropped the magazine on the side table near her sewing chair. She promised herself a nice, long read after lunch—after she finished this spread.

Addie put the last stitches in her work just before noon. Miraculously, though Jake woke up, he was content to coo and gurgle up at the ceiling of his room until she had tied off the last thread and clipped the final row of wicking. She got him out of bed and carried him on her hip into the kitchen, calling up to Mary Alice to come down and get something to eat.

She fed the children and herself and got them both interested in some toys. She went into the parlor and settled herself in her chair, then reached for the Delineator, when she felt something rub against her thigh. It was the envelope in her apron pocket.

She sat back in the chair with a sigh. She’d managed to forget all about Callie Watson and her wedding until just now. She took the invitation out of her pocket and laid it on top of her magazine. She looked at it, cupping her chin in her hand.

She’d known Callie since she was born; the Watsons sat in the pew behind the Caswells at Centenary Methodist, Sunday after Sunday for years. She really ought to go to the wedding. She reached over and thumbed open the card. “William Jefferson Briles,” the groom’s name was. Addie didn’t recollect any Brileses. The boy’s people must be from somewhere else.

Addie wondered where they’d live after they were married. Would William Jefferson Briles settle in Chattanooga, become a partner in his father-in-law’s business? Would he and Callie move into the family pew? Would he be a class leader someday, or even a messenger to the Conference? Or would he follow some strange dream, drag Callie hither and yon, and leave her the day she finally gathered enough gumption to say, “no more”?

Lately, there were whole days at a time when Addie didn’t think about Zeb—when she didn’t wonder what he was doing, where he was living, whether he and this other woman had any friends, any fun, or if they were even still together. Days when she didn’t try to figure out where she’d gone wrong, what signs she’d missed, how she could have done better by him, or by herself, or by somebody.

She turned the wedding invitation over in her hand a few times, then tossed it onto the table beside her magazine. She’d send a gift by Lou. A nice tufted bedspread, most likely. She picked up her Delineator and started looking through the ladies’ evening dresses. Here was one: “Absolutely guaranteed to make the lady wearing it the very cynosure of any gathering, and the gentleman on whose arm she enters the envy of all the swains present.”

*******

George slowed as he approached the lane, then clenched his jaw and turned the wheel, aiming the auto toward Addie’s house. Ned looked at him, a question on his face.

“I’ll just take you on up to the house this time.”

She came out onto the porch, holding the little baby boy. Her daughter trailed behind her, holding onto her apron strings. George braked to a stop and took the car out of gear. Ned got out.

“Well, I guess I’ll see you next time, Ned.”

He nodded and started toward the trail to his house. She was smiling down at the boy.

“Ned, how about taking a loaf of bread to your mama for me?” she asked. “I’ve got you a slice already buttered, with some honey on it.”

Ned shoved his hands deeper in his pockets but didn’t show any signs of leaving without the bread. She went inside and came back out with a bundle wrapped in cheesecloth and Ned’s slice balanced on top. “Here you go.” She handed it to him, and George saw the quick way she glanced away from Ned, toward him. A sliding–away look, like she might be feeling a little bad about something, but not bad enough to say anything out loud.

Ned took the loaf in one hand and the slice in the other. He started to take a bite, but stopped long enough to mumble, “Much obliged.”

“And thank you for the fish,” she said. “I’ve never seen anything quite like it. Will you carve something else for me sometime?”

Ned’s chin fell onto his chest, and he gave what might have been a nod. A flush crept up his neck. He shuffled off around the corner of the house.

Her eyes swung back toward George. He was still sitting behind the wheel of his car, and when she looked at him, he suddenly realized he had no notion of what he might talk to her about.

“George Hutto.” She gave him a slow, greeting nod.

“Addie.” He touched the brim of his hat.

“Fine day for a drive.”

“Yes, I guess it is.” He jerked a thumb over his shoulder. “Somebody building a house across the road from you.”

“Pretty good–sized one too.”

“Yes, pretty good sized.”

The little boy grabbed a fistful of Addie’s hair and tried to put it in his mouth. She craned her head away from him. “Jake, now stop that.” She reached up and pulled the chubby arm away from her hair. He made a squalling sound and tried to snatch his hand away from her.

“No, sir. You stop that,” she told him. He squalled some more.

“Well, I guess I’d better get back,” George said, looking away as he worked the gear lever.

“All right, then,” she said, still wrestling with the little boy. She gave George a sort of distracted wave and went back inside, grabbing at Jake’s hand.

George backed carefully down the lane. Today was Saturday. Why hadn’t he asked her if he could pick her up for church tomorrow? She seemed in pretty good spirits, considering all she’d been through. But maybe that was how it was with most folks—they absorbed the bad in life, then went on. Maybe Addie was going on, that was all. Just doing what people did.

He backed out into the road and put the auto in low. As he drove past, he glanced at the house going up across the road from Addie’s place. This wouldn’t likely be the last house built out this way. He’d heard James Potts was going to divide up a good deal more of his land. Probably a good move, what with the government starting on that dam out by Hale’s Bar and all the talk of the army camp going in just a few miles east. He wouldn’t be surprised if more and more of Chattanooga crawled out this direction.

George felt a vague kind of sadness, thinking of Addie alone in that big house of her daddy’s, just her and the two little children for company. Come to think of it, what made him turn in at her lane today? What did he think he was going to say or do?

Today was Saturday. In a week’s time he’d be back out here, picking up Ned Overby and bringing him home again in the afternoon. Maybe he’d pull down Addie’s lane again. Maybe they’d talk some more. Maybe next time her little boy wouldn’t be quite so cantankerous. Maybe he’d ask for his own slice of bread with some honey on it.

“Old Leather Britches” started running through George’s mind. Pretty soon, he was drumming his fingers on the steering wheel of his car and whistling as he drove back into town.

*******

Addie broke off a corner of the communion wafer and passed the tray to Sister Houser, seated to her right. She had a pretty good spot today, fairly close to the front and no dippers or chewers ahead of her. One Sunday, she’d been late and had to sit at the back, beside Will Tucker. She didn’t know if he noticed her turning the communion cup as he handed it to her and wasn’t sure she cared. It was nearly enough to make you stop taking communion. No use complaining to J. D. or any of the elders, though. They’d just send her to Matthew 26:27 and Luke 22:20 and say the Lord only authorized a single cup when he instituted the Lord’s Supper, and if it was good enough for the Lord and his apostles it was surely good enough for his church. Addie had thought once or twice about asking them if they thought any of the apostles chewed tobacco.

Addie knew she was supposed to be meditating on the sacrifice of Christ on the cross as she partook of the communion, but her mind was an unruly thing today. As she took a demure sip from the cup and passed it to Sister Houser, she had the guilty realization that she’d been trying for the last little while to remember where she’d put Mary Alice’s pinafore that needed mending. She sat a little straighter in the pew and tried to imagine the scene at the Crucifixion: Jesus on the cross, his woeful eyes turned to the stormy heavens; the Roman guard on his knees, realizing this was the Son of God; Mary leaning on the shoulder of the apostle John, her newfound son; Peter and the other men somewhere a little distance off, trying to figure out whether to run or pray.

Poor Peter. Addie could easily picture the look on his face—that scared, confused look men get when they suddenly realize they are about to have to do something they never thought they’d have to do. She remembered the first time Zeb was around when Mary Alice got a soiled diaper. He’d called from the other room, announcing the problem. “Well, there’s some diapers right there on the floor by her bed,” Addie had answered from the kitchen. A minute later when she went into the room with Zeb and the baby, he’d been sitting there, looking from that pile of diapers to his newborn daughter, looking like he couldn’t decide whether to bawl or break for the front door. She’d laughed at him till she had to sit down on the edge of the bed to catch her breath, then shooed him out of the room and gone about her business with Mary Alice.

That was in Nashville, in that little bungalow that had been the servants’ quarters behind the big house on Granny White Pike.

Jake twitched in her lap. She looked down at him, sleeping with his fist bunched in front of his face. Mary Alice was leaning into her side, her face sweaty where it was scrunched against the bodice of Addie’s dress. She brushed a damp strand of hair out of her daughter’s face. Sister Houser looked down at Mary Alice and smiled at Addie. She smiled back. They held each other’s eyes for a moment, the old woman and the young one, as the cup moved steadily along the line of the pews somewhere behind them.

*******

The organist mashed a dense hedge of chords out of the bank of pipes at the back of the church, and everybody stood up, sidling along the pews toward the center aisle. Louisa spoke to the people on either side of her, then noticed Callie Watson standing near the end of the pew, faced by a small half–circle of women. She moved toward them.

“Callie, I was so happy to get your invitation in the mail,” she said. “I sure hope you sent one to Addie.” Louisa kept her eyes steady on Callie’s face so she wouldn’t have to decide what to do about the looks the other women would be exchanging at the mention of her sister’s name.

“Oh, yes, ma’am, I sure did.”

“Well, fine. Guess you and your mama are busy as beavers these days, getting everything ready.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Well. I’m happy for you, honey.” She patted the girl’s hand.

“Thank you, Mrs. Dawkins.”

Louisa walked away. “Ma’am,” Callie had called her. “Mrs. Dawkins.” When, exactly, had she crossed over from “Louisa” to “Mrs. Dawkins?” She felt a faint sadness and, at the same time, a wry amusement at herself. The thought came to her that it had been a good little while since she and Dub had pleasured themselves with each other. If he wasn’t already asleep tonight when she got in bed, she might just do something about that.

*******

George was about to step into the center aisle, but he saw Louisa Dawkins coming and waited for her. As she passed, he gave her a polite little nod and a smile, but she must have been thinking about something else; she didn’t acknowledge him.

Something Rev. Stiller had said was troubling him. At the time it had seemed an offhand remark, really, just an aside from the main gist of his sermon. But it was stuck in George’s mind like a cocklebur in a horse’s tail, and he couldn’t shake it loose.

Rev. Stiller’s text today was from St. Matthew, the fourteenth chapter. He was talking about Christ’s provision for his followers, starting with the feeding of the five thousand and continuing with his rescue of the terrified disciples from the storm on the lake. He’d said something about how, usually, preachers liked to berate St. Peter for the lack of faith that caused him to start sinking when he tried to imitate his Master’s miraculous walking on the water. “But when you think about it,” Rev. Stiller had said, “St. Peter was the only one who had sufficient fortitude to step out of the boat.”

He’d gone on then, talking about Christ’s love and compassion, about how it was displayed even for those who didn’t understand his mission, like the five thousand, or his power, like the storm–spooked apostles. But George had stayed back in that tossing boat, pondering Rev. Stiller’s chance comment. He tried to imagine himself, like St. Peter, seeing Jesus stride across the waves and asking boldly for the ability to join him. No, he decided, it was a lot easier to place himself with St. Andrew, St. John, and the others, fearfully gripping the gunwales of the bucking boat and staring wild–eyed at their crazy fishing partner as he climbed out of the boat in the middle of a roaring gale. Or, even more likely, somewhere at the back of the crowd of five thousand, grateful for the fish and the bread, but otherwise mostly confused about what had just happened.

He was at the door. He nodded at Rev. Stiller and said a complimentary word or two about the sermon. The pastor shook his hand and said he’d see George next Saturday at the YMCA, which reminded George he’d never had that talk with Rev. Stiller about the Bible class, nor had he approached the young Baptist minister about coming in to teach. George smiled, settled his hat on his head, and picked his way down the steps of the church.

*******

Willie felt his stomach grinding. He was glad Bishop Jefferson was talking loud so the noise from his stomach wouldn’t make Mama look at him from the sides of her eyes like she did sometimes. It wasn’t his fault his stomach was empty, and church went too long. But Mama would probably look at him anyway. And Clarice would laugh at him.

Willie bet the white folks were already out of church, maybe home by now. He didn’t know why colored folks wanted to string church out so long. He looked up at his older brother, Mason Junior, sitting all serious and still with the choir. Just for a minute, Willie wished he could be sitting up there with his brother, out from under Mama’s elbow. But up front like that, he’d have to be still too. Everybody would be able to see him. No, that was no good.

He wished there’d been more to eat this morning than a half pan of cornbread that he had to share with his brothers and sisters. Not even any milk to wash it down, just water. Mama said hush complaining. Daddy didn’t say anything, just went on shaving at the kitchen sink. Daddy usually didn’t say much. Even when he was reaching for his razor strap.

Willie listened to Bishop Jefferson. Not the words, really, just the sound of them. That was about the only thing he really liked about church—the way Bishop Jefferson half spoke half sang his words. Willie liked the rhythm of it, the way the words dipped and swooped and rumbled around low right before rising up all of a sudden, like trumpets blaring. Willie liked it that colored folks talked different than white folks. Put their words together different.

His stomach growled again. He liked to listen to Bishop Jefferson, all right. But Willie wished right now he’d finish on up so they could go home.

*******

The pains hit about halfway through the service. As he helped Becky down the front steps of the small white church building, Zeb wondered vaguely what it was about him and women and babies and church services.

He stopped thinking about that when he saw the crimson stains on the back of Becky’s dress as he helped her into the seat of the hired surrey. “Honey? Is something wrong?”

“When was the last time you looked at a calendar?” she said. “It’s only the seventh month, Zeb.” Her breath was coming in quick, shallow pants.

Fear dried his mouth as he yanked the horse around and slapped its rump with the reins. He had to think a minute to remember where he’d seen the small, squarish, two–story frame building that housed the hospital. He prayed there was a doctor around on a Sunday morning.

*******

This post is a chapter from the novel Sunday Clothes, by Thom Lemmons. Sunday Clothes will soon be available for purchase as an e-book at www.homingpigeonpublishing.com

![]()

So Fair and Bright (a weblog) by Thom Lemmons is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

kitchen and sip their tea and stare out the window at the side yard. Once, they had even ventured into the backyard. He had paced up and down with his hands in his pockets, and she had sat in a whitewashed wrought–iron chair, gathered about herself like an owl on a fencepost.

kitchen and sip their tea and stare out the window at the side yard. Once, they had even ventured into the backyard. He had paced up and down with his hands in his pockets, and she had sat in a whitewashed wrought–iron chair, gathered about herself like an owl on a fencepost.