“Well, do you love him?”

Louisa peered at her younger sister, seated on the other side of the quilting frame. Addie ducked her head, but not before Louisa saw the blush.

“Oh, Lou… I don’t know,” Addie said. “He’s awful nice to me. He’s a hard worker, and he makes good money.”

“And he doesn’t clean up too bad either,” Louisa said. She felt the prick of the needle with her fingertip and pulled the stitch through from underneath. She pulled it tight, then placed the needle for the next stitch. “Zeb Douglas is a fine-looking man, and anyone who says otherwise would lie about something else.”

Addie stitched in silence. Louisa thought she could see a faint smile at the corners of her younger sister’s mouth.

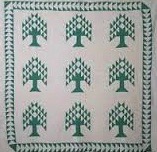

“I tell you, I believe I’ve been working on this quilt all my life,” Louisa said. “If I don’t ever see another tree-of-life pattern, it’ll be too soon. Cora Dickerson down the street got one of those new portable Singer sewing machines, and she’s already started piecing tops with it.”

“Does it do as well as hand piecing?”

“Why, I reckon. She could do three tops in the time it took me to get this one pieced. I’ve been telling Dub I need one. Course, I’ll wind up ordering it from Sears & Roebuck’s for Christmas and telling him he got it for me.”

Addie laughed. “Lou, the way you talk about poor Dub! Anybody’d think you were mistreated, the way you carry on.”

Louisa smiled. “Well, I know. Dub’s a good man. I’ve got few complaints, really.”

The silence stretched, broken only by the soft popping of the two quilting needles as they pierced the taut muslin.

“Lou?”

“Hmm?”

Addie’s lips had that pinched-together, thinking look. Lou thought she knew what was coming next.

“Lou, I… I worry about Zeb and… Papa. Zeb’s not— Well, he’s not Methodist, you know, and—”

“Yes, I know,” Louisa said. “Of course… there’s always George Hutto.”

“Oh, George Hutto!” Addie jabbed her needle through the cloth. “I’m so tired of everybody throwing George Hutto up in my face. I’ve known him ever since grade school, and I don’t see what’s so great about him, even if he does go to the right church!”

Louisa had reached the end of her thread. She looped the needle back through her last stitch and pulled the knot down into the batting, then snipped the extra off down close to the quilt. She reached for her spool of thread and wet the end of the thread between her lips, squinting as she tried to poke it through the eye of her needle. “Well, sounds to me like your mind’s made up on that score, at least,” she said.

“Honey, all I can tell you is this,” Louisa said after awhile. “Comes a time when a woman has to do what’s right for herself, and nobody can tell you what that is, except you. Not me, not Zeb… not Papa.”

Addie’s hands slowed, then stopped. “You mean… You think it might be all right if—”

“I didn’t say that. I don’t know about all right. All I know is you’re a grown woman. This is the 1890s, Addie, and Chattanooga isn’t Istanbul or Peking or someplace like that. A woman has to make her own way, best way she can. And if Zeb Douglas is the way for you, why then—” Louisa sat still for a few seconds, studying the backs of her hands. “Then, maybe that’s what you have to do, that’s all.” She took a few stitches, then looked up, aiming an index finger at Addie. “Now mind, I’m not saying it’s right… or wise.”

Addie’s eyes questioned.

“I’m just saying that you’re eighteen years old, and you’ve got a right to have your say.”

While she stitched, Addie began remembering what she used to do when she was a child. Sometimes, when she felt the need to get away from everyone, she used to climb to the top of one of the sweet gum trees that ringed the backyard of the house. She would climb way, way up to the highest branches, until every breeze that came along would cause her perch to sway and rock. When she was in the top of a tree, Addie could let herself feel freed from the pull of the earth. The thick green foliage hid the ground, creating a special apart-place for her.

Addie longed for a refuge just now. Louisa had made her see that she had the responsibility of choice, and her position frightened her. Maybe she had climbed too high this time. Maybe a storm was blowing up, rattling and shivering among the tops of the trees, tossing her back and forth, a storm that might throw her down from her safe place. Was there a safe place left? Could she really just do what she thought was best? Was it as simple as that? Or would there be other choices beyond this one, other responsibilities and other finalities that would spin off this moment, like the felling of the first domino? What other choices was she making right now, without a chance to see them?

Her vision refocused on the quilt beneath her fingers. Pursing her lips, she took up her needle and made another stitch across the tree-of life.

*******

Zeb Douglas felt like a long-tailed cat in a roomful of rockers. His horse was cresting the final ridge between Orchard Knob and the Caswell homestead. He could look down the slope to the place where their lane peeled off from the road.

He had proposed to Addie the week before as they strolled along the gaslit promenade beside the glassy pond in East Lake Park. It had been a fine Indian summer evening. They’d walked for a long time, her hand in his; the sweet twilight air had seemed like it was whispering secrets in his blood. Then one silence stretched a little long, and before he knew it he was speaking up.

“Addie, you know how I feel about you, don’t you?” he said.

“Well … I think so.”

“Addie, I … I love you. There, it’s out. I want you to be my wife. I want to marry you, if you’ll have me.”

They had walked on slowly; that was the strangest thing, he thought later. To somebody standing on the other side of the pond, they were just two people walking together, moving along as smooth as silk. Who’d have known that his heart was slamming around inside his chest like a penned-up jaybird? He kept his eyes on the footpath, afraid to look at her, more afraid with every step. He started wishing he’d kept his mouth shut.

“All right,” she said.

“What?”

She laughed a little and squeezed his hand. “I said all right. I’ll marry you.” He had looked at her then, and she was smiling. “I will,” she repeated. She stopped walking and turned to face him, taking both his hands in hers.

Right then, he thought he might bust wide open. He felt his grin getting all long and rubbery. He wanted to jump up and down like a little kid on Christmas morning; he wanted to spin around in a circle and holler. He pulled her to him and squeezed her tight. Her wide-brimmed hat fell off, and he giggled like a schoolboy, snatching it up and planting it askew on her head.

“Oh, Addie, you don’t know how you’ve just made me feel! I’m the happiest fellow in Hamilton County!” He planted a chaste but sincere kiss on her lips.

“Zebediah Douglas!” She pushed him away. “You’d best mind your manners!”

“Aw, I’m sorry, Addie,” he said, grinning. “I just couldn’t help it.”

“Well,” she said, a smile stealing across her face, “I guess I didn’t really mind all that much. Just don’t get too fresh, that’s all,” she said.

“Zeb,” she said a few minutes later as they strolled on down the walk, “when are you going to tell Papa?”

And he hadn’t drawn an easy breath since. His horse started down the curving slope of the Caswell’s drive.

Jacob Caswell could sure do worse for a son-in-law. It wasn’t as though Zeb didn’t have prospects. He’d just been promoted to manager of the Murfreesboro office. He now had three other agents under him, and the company principals were very pleased with his work. He was an up-and-comer in the agency force.

You let your daughter marry me, and I guarantee you’ll never see her taking in washing while her sorry husband’s off running with his coon dogs…

But Jacob Caswell was a dyed-in-the-wool Methodist, and that was that. Every time Zeb called on Addie, he could feel her father’s hostility to his religion chilling the back of his neck. Even when he didn’t go in the house, he could sense Jacob’s disapproval brooding over him like a summer thunderhead.

He tried to tell himself not to take it personally. Addie had warned him repeatedly of her father’s uncompromising denominational compunctions.

She had told him about the time, one raw winter’s night, when a knock came on the front door of their home. Outside was a man huddled against the sleet, clutching his collar about his neck He told Addie’s father that his wagon was broken down just beyond the crest of the rise; a wheel had come off the axle. Could he board himself and his horse for the night? Addie’s father had brought the man in and given him a cup of hot coffee. He was just about to pull on his mackintosh and go out into the night to help the stranger bring in his horse when he chanced to ask the fellow what brought him to these parts on such a bitter evening.

The man answered that he was a circuit preacher for the Church of Christ and that he had come to conduct a revival service.

“Papa got a sick look on his face,” Addie said, “and started taking off his coat. The man looked at him kind of strange, and Papa said, ‘Sir, my religious convictions prohibit me from rendering aid to a person I believe to be a teacher of heresy. I am deeply sorry, but I cannot help you this evening.”’

Addie told how her father sent that man back out into the sleet and shut the door behind him. Jacob Caswell leaned against the closed door for several minutes, then slumped down in the hall chair with his head in his hands. “He felt real bad for the man,” Addie said, “but that’s just how he is about what he believes.”

Now Zeb was here. He reined his horse to a halt and eased down from the saddle. He looped the reins over the porch railing and straightened himself, staring at the front door of the house. He had to ask for Addie’s hand; it was the only honorable thing to do. He knew she would marry him, but he also knew she wanted the proper forms observed. That’s just the kind of girl she was.

He took a deep breath, then another. He dusted off his hat and put it back on his head. He straightened his tie and tugged his coat down all around. And then, like a man going to the gallows, he climbed the front steps.

He raised a knuckle to knock on the frame of the screen door, but before he could, the heavy inner door swung inward. Addie stood there, dressed in her newest crinoline-and-lace. At the sight of her, he almost forgot his nervousness. But then he saw the set of her eyes and the tense way she looked over her shoulder toward the parlor, and every trace of moisture instantly evaporated from his throat.

“Come on in,” she said, standing aside and trying to smile. “Papa,” she called, “Zeb’s here.”

Rose stepped into the hallway as he entered, drying her hands on a dish towel. Her eyes glinted from Zeb to Addie, then toward the parlor where Mr. Caswell waited. She ducked back into the kitchen.

Zeb had to concentrate on what his knees were doing as he paced toward the parlor. He expected Jacob Caswell to be seated in his red leather wingback chair, his face buried in the Chattanooga Times as he had been situated on the other rare occasions when Zeb had been admitted to the parlor. But this time he was standing, his hands clasped behind his back. He still wore his dark Sunday suit, his tie knotted at the throat. He was scowling at the floor, and he looked up as Zeb entered, with Addie following three paces behind.

“Papa,” she said, “Zeb’s here, and he wants—”

“I know why you’re here,” Jacob said. “I’m not blind, you know.”

He glared at Zeb. Zeb felt his Adam’s apple bobbing up and down like a fishing cork. Zeb thought of the words he had rehearsed on the way here. He drew a chest full of air and tried to square his shoulders. “Mr. Caswell, it must be apparent to you that your daughter and I—”

“It’s apparent to me that my daughter has set her mind on marrying you, Mr. Douglas. Only a fool would think otherwise, and I don’t much believe I’m a fool.”

“No … no, sir. I expect not.”

“She’s eighteen years old,” Jacob said, his eyes glittering toward Addie, “and I know better than to try to talk a woman out of something her mind’s set on. That’s the one piece of advice I’ll give you, Mr. Douglas: don’t try to reason a woman out of something she already wants to do.”

Zeb swallowed. “Uh … thank you, sir.”

“But I’ll tell you this, young woman,” Jacob said, aiming a finger at Addie. “You know how I feel about this man’s religion. You were raised in a sensible Methodist family. If you choose to join this man’s church—”

“Ah, we don’t call it ‘joining the church,’ sir,” Zeb said. “We believe God adds the obedient to—”

“Zeb! Not now!” Addie said.

“Never mind,” said Jacob Caswell, his eyes still on his daughter. “You can call it joining, or being added, or whatever other fool thing you fancy, but I’ll say this once and for all: if you follow him into this religious group of his, you best reckon all the consequences. You best make sure you love this fellow enough to live with the consequences.”

No one spoke for a long time. Addie leaned against the doorframe, her hands behind her back. Zeb wondered if she was holding on to the woodwork to keep from falling. Her face was as white as the high lace collar of her dress, and her eyes looked big and dark as they flickered back and forth between him and her father.

Then Addie stood away from the doorframe. She walked toward Zeb and took his arm. She turned to face her father.

“Papa, I love him. I mean it.”

Jacob Caswell grunted, shoved his hands into his vest pockets, and stalked past them. He grabbed his hat from the hall tree and yanked open the front door. They heard his rapid strides thump on the front porch and down the steps.

A long breath went out of Addie, and her head fell on Zeb’s shoulder. “Well, that’s that,” she said.

Zeb couldn’t speak. He put an arm around her and patted her. Twice.

*******

This post is a chapter from the novel Sunday Clothes, by Thom Lemmons. Sunday Clothes will soon be available for purchase as an e-book at www.homingpigeonpublishing.com