Addie walked to the window and peered as far as she could down the lane and along the road toward town, trying to see some sign of Dub’s headlights. Nothing. She paced into the parlor and looked at the mantel clock. Half past eight.

“Mother, when are they coming home?”

“I don’t know, honey. Your Uncle Dub said he’d be back by dark.”

“It’s been dark a long time.”

“I know.”

“Why aren’t they back?”

“I don’t know. Why don’t you go finish your lessons?”

Mary Alice turned away and went back toward the kitchen, her head down. Addie’s voice was sharper than she intended. Her anxiety was infecting Mary Alice, most likely. Addie was trying to keep ahead of her worry, but the later it got, the more it gained on her.

The telephone made its rattly ring. Addie stepped quickly into the entryway and pulled the earpiece off the hook. “Hello?”

“Addie, it’s Lou. Dub and the boys just left for your place. He told me to call and tell you, so you wouldn’t worry.”

She felt a rippling flash of relief, followed quickly by aggravation. “What kept them so late?”

“Dub said the traffic down the mountain was real bad after the races were over. He said they got back as quick as they could.”

“Well, all right. They’re on their way?”

“Yes. Dub said Jake had the time of his life.”

“I don’t doubt it. All right, then. Thanks for calling.”

Addie replaced the earpiece on its hook. She wouldn’t have agreed to this at all, but Dub promised he’d keep Jake with him every minute of the time. For weeks and weeks now this auto race foolishness had been the only thing you heard anybody talking about; it had even crowded out the Prohibition vote as a topic of conversation. But now that the commotion was over and Louis Chevrolet and all his millionaire sporting friends were packing up to go back wherever they’d come from, maybe things would settle down to normal again.

She stuck her head in the kitchen. Mary Alice was hunched over her school tablet in the pool of light from the hanging bulb. “That was Aunt Lou. They’re on the way home.”

No acknowledgment. Well, let her have her mad; she probably deserved it.

Addie went back to the parlor and inspected her day’s work. Two more spreads ready to ship to Mr. Lawlis. It was a lucky day for her when the Chicago businessman happened into Dub’s store and saw her bedspreads. He’d let her know more than once he’d be happy to take more than the two spreads per month she’d been sending. But Dub had helped her get started, not to mention he was family. She wasn’t about to throw him over for some fancy dresser from up north, no matter how promptly he paid.

She heard the sound of Dub’s Model T. She went to the front door and stepped out onto the porch.

Dub pulled up in the yard and the doors flew open. Jake and his cousin Ewell chased each other around and around the automobile, imitating the sound of racing cars.

“I’m T. J. Gates, from the Buick Racing Team,” Jake hollered.

“And I’m Loueee Chevrolaaaaay,” shouted Ewell.

“All right, you two,” Dub said. “The races are over; time for the cars to go back in the shed.”

Jake stopped in the middle of the yard and windmilled his arms, still making race car noises.

“Jake, you better tell Uncle Dub ‘thank you,’” Addie said.

“Thank you!” he yelled, without turning around.

“Thanks, Dub, for taking him,” Addie said.

“No trouble, Addie. We had a big time, didn’t we, boys?”

“What do you hear from Robert?” Addie said. “How’s Vanderbilt?”

“Fine, except for the classes.” Dub laughed and shook his head. “Takes after his daddy, I guess.”

“Well, Jake, you better get in the house,” she said. Jake immediately took off on another lap around the Model T.

“Ewell get in the car, son. We better get home. Sorry to be so late, Addie. The traffic—”

“Yes, Lou called. Jake! You better get in this house right now, young man, or I’m fixing to flatten your tires!”

Jake sputtered up the front steps and sprawled on the porch at her feet. “I’m out of gas, Mother.”

She waved at Dub as he backed out of the yard, then bent over and poked the boy in the ribs. “Out of gas, huh? Out of gas?”

He giggled and squirmed, trying to evade her tickling. She got him up and pointed him toward the front door. “I don’t guess Uncle Dub fed you anything, did he?”

“Sure did. They had barbecued turkey legs up there, and lemonade, and cider, and corn on the cob, and—”

“All right, all right. I get the picture.”

“Oh, you should’ve seen it, Mother! All those cars, and the engines just a–roaring, and the dust flying out from under their wheels when they made the turns—”

“I’ll bet you were in hog heaven.”

“There were even some drivers from Chattanooga. Uncle Dub knew ‘em. Eddy Kenyon, and Charles Duffy, and—”

“And you’d best get those clothes off and get ready to get in the tub. You’ve probably got dust in places you can’t even show decent folks.”

“—and the Buick Racing Team! All the way from Detroit, Michigan, Uncle Dub said. And Louis Chevrolet. He’s French. Mother, where’s Detroit, Michigan?”

“North, a ways. Now get on upstairs.”

“Oh, Mother, it was just bully, is what it was. Bully all the way down to the ground!” He pounded upstairs, shedding clothes as he went. She looked after him, shaking her head. He’d be talking about this for weeks, most likely. She’d be surprised if he slept a wink tonight.

A little while later, she went to the kitchen. It was getting late. Mary Alice needed to be getting ready for bed. “About finished, dear?”

“Yes, ma’am.” Mary Alice closed her book and sat with her hands in her lap, staring down at the dull blue cover of the McGuffey Reader.

“What’s wrong, honey?”

Mary Alice sat very still, not even moving her eyes. Addie was fully prepared to hear about how she’d hurt Mary Alice’s feelings with her sharp tone just before the phone call came from Lou. She was prepared to respond to why Jake got to go to the car races with Uncle Dub and Ewell and she had to stay at home and do her schoolwork. But she wasn’t quite ready for what her daughter actually said.

“Sarah Frances Tanner says I don’t have a daddy.”

“Do what?”

“She does. She says I don’t have a daddy.” Still, Mary Alice wouldn’t look at her. “At recess today, she said it. And at lunch she said it to Lucy Wilkes. She told her I don’t have a daddy.”

Addie felt as if a place in the center of her chest was emptying. She stepped to the table and quietly pulled out a chair, then sat. She put her hands on the table and laced her fingers together, then spread them out, palms down. She took a deep breath and let it out slowly.

“So, Sarah Frances said that, did she?”

“Yes, ma’am.” Now she raised her eyes to her mother’s. “Why doesn’t my daddy live with us, like Sarah Frances’s and Lucy’s?”

“Sweetheart—” Where on earth to start? “Honey, do you remember your daddy at all?”

She pursed her lips. “Just a little. I remember some sparkly paper. Was that Christmas?”

Addie gave a sad little smile and a nod. “Yes, dear, that was Christmas. Anything else?”

She twisted her mouth back and forth, then shook her head. “No, I think that’s all.”

“Honey, your daddy traveled a lot. He was gone more than he was home, even after you were born. And then, one day—”

The old hurt surprised her, sidetracked her with its sudden intensity. As if it had been waiting for a chance at her, and this was it.

“One day, he decided he didn’t want to come home anymore.”

“Was he mad at us?”

“Oh, no, sweetheart, not a bit. Not at you, anyway. No, don’t ever think that.”

“Was he mad at you?”

A place in her throat was starting to ache. She swallowed. “I guess he was, in a way. Maybe not mad, exactly, but … I guess he was just sad, maybe.”

“Did you do something bad to him?”

“No, I didn’t. At least … if I did, I didn’t know what it was.”

Mary Alice’s forehead wrinkled. “Mother, was he ever around after Jake was born?”

“No, honey. He wasn’t.”

“Well, what’ll Jake do? He won’t even have shiny paper to remember.”

No, not even that. “I … I don’t know, honey. I don’t know.”

She reached across the table, put a hand on her daughter’s arm.

“Mary Alice, now listen to me. What happened with your daddy and me wasn’t your fault. And it’s none of Sarah Frances’s business, or anybody else’s. You’re a sweet girl, and I love you, and you just remember that. All right?”

Mary Alice looked at her a long time. “Yes, ma’am.”

“All right, then. You’d better go get ready for bed. School tomorrow.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

She dragged her books and paper off the table, tucked them under an arm, and wandered out of the kitchen, toward the stairs. Addie watched her go until she rounded the corner. When she heard Mary Alice’s feet on the stairs, she put her face in her hands.

She wondered why her own hurt hadn’t taught her how to soothe her daughter’s. You’d think I’d know something to say to her, Addie thought. But Mary Alice’s wounds were in a different place, had a different shape. And then Addie felt the raw and livid place inside her, the part of her that felt insulted that her daughter should even notice the lack of a man who’d cared so little for her—or if he did care, it wasn’t in any way that made a practical difference. Just one more way I’m not good enough, she thought. Just one more thing he’s done to me: leaving me here to explain something to a nine-year-old girl that her twenty-nine-year-old mother has never been able to explain to herself.

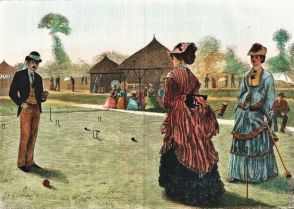

She got up from the table and wandered over to the sink. She’d tacked a calendar to the wall above the sink, beside the window that looked out onto the backyard and the tree line beyond. Peabody’s Dry Goods sent them out; they had a different illustration for each month of the year. The illustrations were in the style of the old Currier & Ives prints; this month it was a party scene, men and women playing croquet or some such game in the foreground, and a group gathered around some kind of table in the background. A church social, maybe. There wasn’t a title to it. The men were all wearing top hats, and the ladies’ dresses were old–fashioned, flared affairs with huge sleeves ballooning between the shoulder and elbow. And they were all wearing gloves. Didn’t look too practical for croquet, come to think of it.

Mary Alice’s birthday was coming up in a few weeks. Addie would make her a great big cake and invite all her little school friends over. Maybe she’d pay Ned Overby a little extra, get him to stay after his wood chopping and turn the crank on the ice cream bucket. She’d think of some party games the little girls could play, and she might even try to sew a special frock for Mary Alice to wear, just for the occasion. Maybe she’d see if Lou would loan her Lila’s services to decorate and get ready for the event.

She stared out the window at the dark yard, the darker trees. She found herself thinking of Carolina Clark.

Her name was Carolina, like the state, she said, and she was very particular about the correct pronunciation. She was from somewhere up north. She came to Chattanooga when Addie was still a little girl to be the second wife of John Larimore Clark, a wealthy landowner whose first wife died from consumption. Addie remembered the first Sunday John Larimore Clark brought his new wife to church at Centenary Methodist. Addie remembered that even as a child, she thought of Carolina Clark as a small woman, and very pale. She wore big, wide–brimmed hats to church.

Carolina had odd ways, even for a Yankee. She was rarely seen outside the big, three–story house on Walnut Street that she shared with her husband and stepfamily. Some said she almost never left her own room. She was subject to headaches and would spend weeks at a time in bed with the curtains and shutters drawn.

But one of her strangest habits was that she never went anywhere or did anything, indoors or out, without wearing gloves. Naturally, most of the women at Centenary Methodist wore gloves to church. But even at meals, people said, Carolina Clark kept her hands concealed in gloves of silk or fine linen.

On a Sunday afternoon in the middle of the summer, right after dinner, Carolina Clark got up from the table and announced that she was going to her room for her usual nap. The servants were away, her husband was traveling on business, and the children were in their rooms upstairs. Sometime that afternoon, Carolina rose from her bed, removed her Sunday clothes, walked outside, and threw herself down the eighty–foot well in the backyard. When her body was removed a few days later, all she was wearing were her white silk gloves.

That was what everybody knew, but what nobody said. At her funeral service, the preacher spoke of her as “a quiet woman who troubled no one.” But the thought of her troubled Addie, even as a young girl. What would make anybody want to do what Carolina Clark had done, she wondered. What dark voices whispered to her from the well, and why didn’t anybody else hear them, or know? Why wasn’t there anyone to shoulder a corner of Carolina Clark’s quiet desperation?

Addie suddenly felt very tired. She had some spreads she ought to work on, now that the house was quiet, but the thought of going into the parlor and threading her needle seemed arid and burdensome. She thumbed the button by the door to switch off the kitchen light. She tested the lock on the front door, then went to her room, turning out lights on the way.

*******

The man across the desk picked up the carvings as if he were handling Babylonian pottery shards. He held them up this way and that way, looked at them from every possible angle. He was a big man; his face was red and sheened with perspiration. His hands were beefy, but he handled Ned’s work like an acolyte might handle sacramental vessels.

“He’s got drawings?”

“Yes, right here.” George laid the leather portfolio on the desk between them. He was proud of the portfolio. He’d ordered it from one of the catalogs Professor Gaines suggested. Ned had grinned for a whole day when George gave it to him.

The man opened the portfolio. His lips made little pursing motions as he looked at Ned’s drawings. He would flip quickly through several sheets, then pause, slightly squinting one eye or stroking his upper lip as he studied a piece more closely.

“The style is a little naive, of course … that’s to be expected. But my! What a sense of line.” As he looked at the drawing, one of his hands strayed to the carving he’d been examining: a deer springing over a log. George smiled. It was hard to keep from touching Ned’s carvings.

“Oh, so he’s done some charcoals … Hmm … Yes.”

He closed the portfolio and looked up at George. “Well, Mr. Hutto, I must admit I was dubious when I received your first telegram. If Percy Gaines weren’t an old friend— But it appears to be just as you and Percy say. The boy is very, very talented.”

George leaned back in his chair. “Well, Professor Koch, I— It’s good to hear you say so.”

“May I speak with him?”

“Oh, well … he isn’t here. That is, he didn’t—couldn’t come with me.”

Professor Koch arched his eyebrows.

“His father needed him, you see. It’s spring, and that’s the time Perlie—Mr. Overby, the boy’s father—when he sells his hides, and—”

Professor Koch had bridged his fingertips and was staring at George with a blank expression.

“Well, at any rate, Ned couldn’t come with me to New York, you see. I was hoping you could look at his work and tell me— And you have, of course, and so … I was hoping …”

Professor Koch looked at him a bit longer, then cleared his throat with a delicate sound. “Mr. Hutto, you must realize. Our institute has certain standards.”

“Yes, of course.”

“To be considered, each candidate must undergo a personal interview by the faculty.”

George nodded.

“He must agree to the terms and conditions of enrollment. He must be made to thoroughly understand what we expect of our students.”

George took a handkerchief from his pocket and dabbed at his lips.

“Still …” Professor Koch took up the deer carving. He ran a palm over the deer’s back, ran a fingertip along the delicate, perfect curve of the neck. “I suppose, given the geographic challenges involved …” He put down the carving and aimed a forefinger at George’s chest. “The tuition for the first quarter must be completely prepaid.”

“Oh, yes, sir. That will be no problem.”

“And we’ll need letters from a teacher, and from Percy, and—”

“Yes, I’ve already spoken to them, Professor.”

Professor Koch leafed through the portfolio some more. “Yes. Extraordinary eye this boy has.”

George leaned back in the chair again and smiled.

*******

This post is a chapter from the novel Sunday Clothes, by Thom Lemmons. Sunday Clothes will soon be available for purchase as an e-book at www.homingpigeonpublishing.com

![]()

So Fair and Bright (a weblog) by Thom Lemmons is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

kitchen and sip their tea and stare out the window at the side yard. Once, they had even ventured into the backyard. He had paced up and down with his hands in his pockets, and she had sat in a whitewashed wrought–iron chair, gathered about herself like an owl on a fencepost.

kitchen and sip their tea and stare out the window at the side yard. Once, they had even ventured into the backyard. He had paced up and down with his hands in his pockets, and she had sat in a whitewashed wrought–iron chair, gathered about herself like an owl on a fencepost.